Made of Stone

How the Gunks Volunteer Trail Crew is Changing the Way You Approach Climbing

Dick Williams has been climbing in the Gunks since 1958, and when you visit his office you’ll find signs of it. Pictures of Williams and friends out climbing dot the walls, huge bookshelves taking up the majority of the wall’s real estate are filled with old guidebooks, rows of CDs containing Gunks photos, and stacks upon stacks of bound journals and logbooks documenting everything from the area’s crags to trail work, which was what had brought me to his doorstep. I wanted a peek at his rumored photo gallery, which he started in 2005, and his logbook, which he started in 2002 listing all the work the Volunteer Trail Crew had done.

He pulls out a photocopied booklet of 12 oversized pages from his Trail Work Log, and hands me the stack to look through. Meticulously documented, with ruler-straight lines drawn in, this log tracks not only the volunteers that came out on which days and for how long between 2002 and today, but which areas the crew worked on, accidents sustained and man-hours put in.

I look through the pages a little awe-stuck at the sheer time it took to document the work done, not to mention the actual hours of manual labor. Williams sits next to me and looks on as I flip through his work, occasionally stopping me to add and note here or there. He finally sits back, adjusts his glasses with a kind of proud revelry, and then looks up. “I just like to document things,” he says.

When Williams first arrived on the scene, a busy weekend would spike to about 40 or 50 climbers, but typically there were few more than a dozen. That’s a stark contrast to today where you sometimes find lines of climbers at the base of popular routes on busy weekend days.

The fruits of labor. Even after the first day of trail work on the High E staircase in May 2013, you can start to see progress. Photo: Dick Williams.

Another difference: As Gunks climbing was developing in those early days, climber didn’t typically walk along the base of the cliff to access the routes like we do today. The cliffline was overgrown with vegetation; it was nearly impossible to do so. Rather, climbers would head straight up from the carriage road picking their way through the talus to the route they wanted to climb. Then they would climb the route to the top and walk off the backside, picking up the carriage road to loop all the way back around again.

But as climbers in those early days started to cut timesaving corners by hacking their own trail along the base, the environment along the cliffline began to suffer. “Over the years the trail along the cliff base got wider and wider and then erosion began,” says Williams. It was something Williams noted in those earlier days, but it wasn’t until 1999/2000, when he sold Rock and Snow to Rich Gottlieb, that he had enough time to commit to working on the trails.

“It was time to act, time to actually do something constructive,” says Williams as he pulls out a guide with route and area names highlighted in different colors. “I began by drawing up a proposal for the Mohonk Preserve with a plan to restore the entire Trapps and Near Trapps,” says Williams as he points to the highlighted names in the book, “showing areas on immediate repair (in red), areas that will need repair (blue) and areas that are good for the time being (green).”

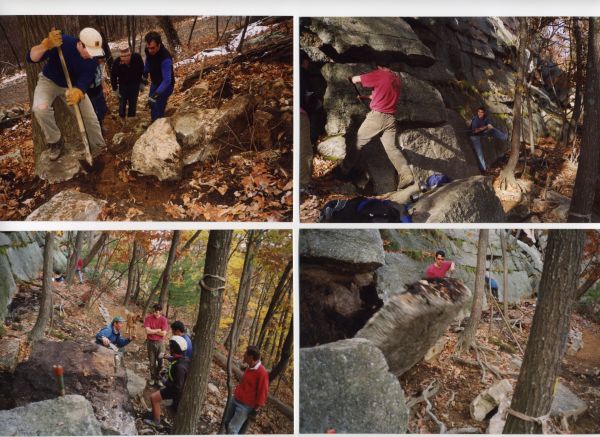

A series of shots from trail work done on the V3 trail in 2006. Photo: Dick Williams.

He also listed other projects for the Preserve: areas that needed retaining walls or major leveling, areas that need protection of exposed tree roots, areas that just needed repairs. It started to snowball into a much larger project: to construct, repair or rebuild most of the existing approach trails, and to close off many of the maverick trails up to the base of the cliff. The idea was simple: funnel everyone approaching or descending from the cliff to one of these designated and well-maintained trails and reduce erosion and damage to the cliffline environment. For this proposal, the Mohonk Preserve awarded Williams the Thom Scheuer Stewardship Award in 2001, an award of which Williams was proud, and for good reason. This proposed work turned into real work done by Williams alongside a huge crew of volunteers over the years. It changed the way climbers approach Gunks crags.

Work began in 2000 and Williams’ meticulous documentation skills came in handy as he tracked not only progress, but also the volunteers that came out to help and man-hours put in. In the early years of the trail crew, tools were limited. They only had ropes, pulleys and pry bars, so they couldn't move big stones. But after the first year, the AMC donated a grip hoist and this was a game changer; that and more manpower allowed the crew to move some incredibly huge pieces of stone. Many of the stones average about 500 to 1000 pounds, many of which are one or two tons. One stone below Three Doves that the crew moved was 8,000 pounds, and they moved another 8000-pounder that was in the way to Madame G’s (Madame Grunnebaum’s Wulst). According to Williams, the largest stone moved to date, was just last month when they started the new trail to Arrow. The big stone you can see at the base weighs in at about 10,000 pounds, and took four grip hoists and very good rigging management to accomplish.

The new Arrow Trail begins. Here Mark Arrow, Carol Yang, Williams, Claude Suhl, working on moving/placing a 10,000 pound stone. 2016. Photo: Stu Soycher

The finished product. This 10,000-pound baby is the largest stone moved to-date. 2013. Photo: Stu Soycher

More equipment and more volunteers meant more projects. By 2007, the crew had repaired most of the entire base of the Trapps and Nears. By 2010, they were well into major rebuilds of staircases, beginning with the Middle Earth trail, including the area over to and up to Red Pillar. 2011: Never Never Land area, and V3 trail and base area including the Wild Horses/Raunchy area. 2012 turned into a beast year when Williams decided it was time to tackle the Mac Wall. The crew built a new staircase and restored the entire area from Three Pines over to Tough Shift, which according to Williams was in horrible condition. Then in 2013, Williams decided it was time to get started on what turned out to be the longest project, rebuilding the High Exposure staircase and reconstructing the base of the cliffs from The Last Will Be First all the way over to the High E rappel base. That project, in its entirety, took two years.

Before the High E Trail work. 2013. Photo: Dick Williams.

Before the High E Trail work. 2013. Photo: Dick Williams.

After the High E Trail work. Reconstruction work completed at base Directississima and of Hi E rappel. 2014. Photo: Dick Williams.

High E Trail Work Project in August 2014. Al Limone, filling in the paver gaps at base of Hi E rappel, Rick Cronk in back. Photo: Stu Soycher

Last year, the crew tackled the construction of a stone staircase up to Madame G’s to replace a dirt trail. This is one of the few areas they have returned to a second time over the 16 years, and the struggle here was finding the stones. “There was no boulder field near by so we had to harvest every stone from along the carriage road, haul/drag them to the base of the trail and then haul each one up to be placed,” says Williams. It was the most difficult task to date, and took a year.

High E Trail Work Project, moving a monster stone, Mark Arrow, and Rick Cronk. 2013. Photo: Dick Williams.

The complicated styles of rigging, moving and hauling giant stones is time-consuming and labor intensive; occasionally there were injuries, 2010 being to worst year with broken ankle and twisted knee. Hundreds of man-hours go into these projects. In 2015 alone, Williams recorded 1,146 total man-hours. Disregarding 2000 and 2001, which Williams did not record, the volunteer trail crew has logged 9,415 man-hours to date, and that number is going up. By the end of the year, and the end of the Arrow trail project, the crew will likely surpass 10,000 hours. That adds up to about 13 months of 24-hours-a-day, seven-days-a-week worth of labor.

High E Trail Work Project, moving a pretty big stone, Claude Suhl on the grip hoist. 2013. Photo: Stu Soycher

While Williams has been the organizer over the years, he attributes the volunteers as the driving force behind all these projects. “I have so many great memories of great work with the greatest bunch of people you can imagine,” says Williams. “They are supremely dedicated and talented, the Gunks are very lucky to have them.”

There are too many to name, and an incredible amount of hours volunteered. But the work done stands as a reminder to the thousands of hours of hard labor. So next time you’re hiking to the base of the cliff, admire the stone steps, take a look at the base of the cliff and notice all the hard work right below you feet. And if you’re feeling really good-natured, buy the trail crew a beer.